The entry of non-traditional funders – and the availability of non-traditional exits – has altered medtech, though probably only temporarily.

The ease with which private device makers can currently obtain vast amounts of funding is the result of a convergence of several factors, including interest from investors that have not previously been major players in the sector, and increased options for exits.

But this climate will not last forever, and it is worth considering what might happen to the sector when at least some of the cash available dries up.

“We think medtech has long been an underserved market,” says Darshana Zaveri, a managing partner at Catalyst Health Ventures, a US-based venture firm that has been active in the device industry for many years. “It’s really good to see capital flowing back into medtech. And the entry of non-traditional capital sources into the early stages is also fueling some of this activity.”

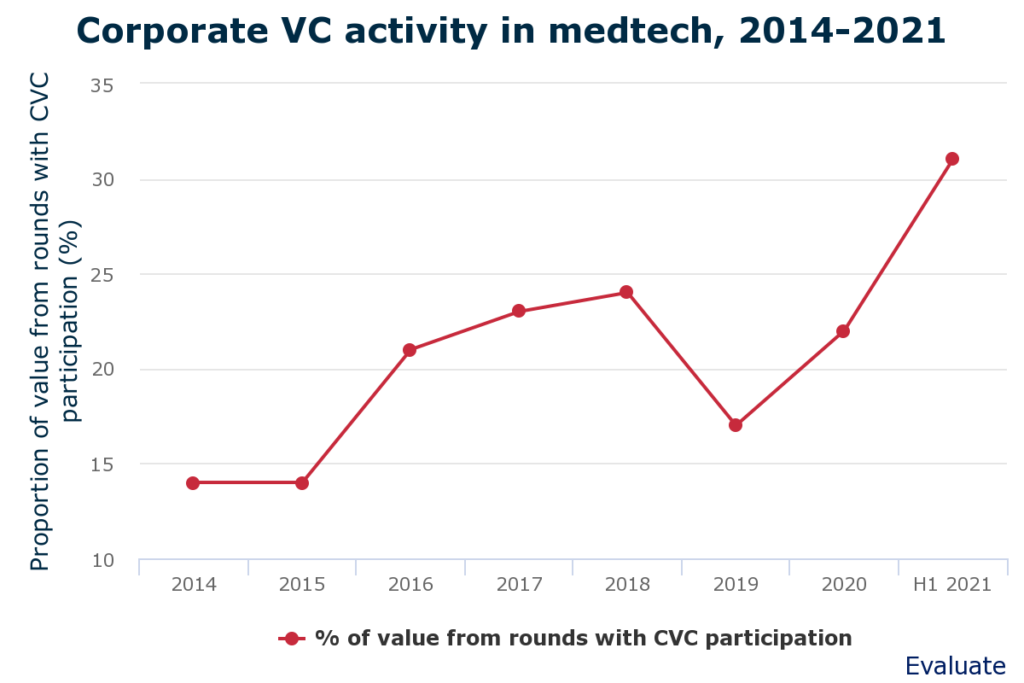

Ms. Zaveri and her colleague Josh Phillips, also a managing partner at CHV, believe that the flood of cash into the device sector was spurred by the increased involvement of corporate VCs.

“There’s been a lot of strategic activity in this space in the last four to five years,” says Mr. Phillips. “They have come into venture investing, recognizing that there has been a lack of investors in the space in the early stage.”

Active corporate funds act as a lure for other atypical investors, making it easier for other sources of capital to follow what they think of as smart money, Ms. Zaveri says. “We’ve seen hedge funds or family offices – not traditional medtech investors – following those strategists into deals. There’s lots of money, but from sources that weren’t traditionally present five or 10 years ago.”

Funder storm

This chimes with what Evaluate Vantage has found. In the first half of this year 31% of the venture cash raised by device companies came from rounds including at least one corporate – a higher percentage than ever before. This trend ought to continue for some time, given that the pandemic was something of a windfall for many of the larger groups. They have “piles of Covid cash”, as Mr. Phillips puts it, and they need to spend it.

Several of this year’s largest funding deals have included other non-traditional investors. The Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan invested in Kry’s $316m deal, for example, and Akili’s $110m series D came partly from Temasek, the investment company owned by the government of Singapore.

All of this risks driving valuations higher, though Ms. Zaveri says, “They’re not frothy by any means, particularly if you compare medtech to pure tech, or biotech.”

The other piece of the puzzle is a sudden panoply of exit options. The public markets have been unusually receptive to floating device companies, with the latest rush to the stock exchanges beginning in late 2018. And the sums raised have soared, data compiled by Evaluate Medtech show (Floating medtechs go big or go home, July 14, 2021).

Medtech has not, in the past, been a big sector for IPOs, Mr. Phillips says. “Typically, companies in this space need to generate substantial revenue before they go public, but we’ve seen in the last couple of years that companies are getting out earlier.”

The dramatic incursion of special purpose acquisition companies into the sector is another factor. Ms. Zaveri points out that blank-check firms provide a potential exit avenue for medtechs that simply did not exist before. All these elements put together are fueling a white-hot investment climate.

Sooner or later

A big question for investors is how long this state of affairs might continue. While there may be no imminent risk of easy capital drying up, sooner or later the purse strings will tighten.

“It’s hard to say how long this is going to go, but what we have seen in the past is non-traditional capital comes and goes,” says Mr. Phillips. “And it’s not necessarily based on success in medtech. Where we have seen capital come and go before, it has been as a result of other things than what the underlying businesses were doing.”

The financial crisis of 2007, and before that the bursting of the dotcom bubble in the early 2000s, caused strategists and large asset managers to reassess what they were doing, he says. Something similar could be triggered once again by macroeconomic factors.

On the exit side, any large crash would scotch most if not all medtech flotations, and Spacs would have a hard time finding backers, too. Even absent a financial catastrophe, the Spac trend might be short-lived, given the high rates of investor opt-outs and the less-than-stellar stock performance of companies that have chosen to go down this route (Why some Spac deals are not all they’re cracked up to be, August 11, 2021).

Should this pullback transpire, the traditional medtech-specialist VC shops will still be plugging away. CHV itself favors early-stage deals, starting with $2-3m checks for seed to series B rounds and reserving a further $6-8m for later financings. They might not grab the headlines, but small, early deals are the real underpinning of device innovation.

Even so, private medtechs seeking funding right now would be foolish not to try to fill their coffers during a frenetic funding boom that will not last for ever.